The Story behind the Stone – the families, estates and stories of Kirkmichael, Cullicudden, the Black Isle and beyond

The Remarkable Barkly Family – and their Kirkmichael Origins

text: Nick Hide photos as given below each image

Sir Henry Barkly, GCMG KCB FRS FRGS, Governor in turn of British Guiana, Jamaica, Victoria and Mauritius and the Cape

Colony, and MP.

Gilbert Barkly, merchant and spy.

Aeneas Barkly, partner in Davidson & Barkly, the great West India merchants.

Captain Charles William Barkley, trader, adventurer and explorer.

These are some of the more prominent of the Barkly or Barkley family, many of whose earlier members are buried in

Kirkmichael. The family was associated with the parishes of Resolis and Cromarty for more than a century, and the handsome

Barkly enclosure at Kirkmichael is the earliest manifestation of the influence that the family would have not just locally on the

Black Isle but around the world.

There are five known gravestones with monumental inscriptions located at Kirkmichael with links to the Barkly family. There are three table stones and one small headstone located inside the Barkly enclosure which adjoins the Grant of Ardoch enclosure. There is also one flat stone just below the turf located outside the family enclosure. We know of more family members buried at Kirkmichael, right up to the year of 1850, and either they are in unmarked graves or there may be stones still deeper below the turf yet to be discovered.

The Barkly enclosure is surrounded by the wall of the Grant enclosure to the east and by iron railings on the other three sides. The iron railings are possibly 19th century additions.

Railings surround the Barkly Enclosure at Kirkmichael; behind lies Udale Bay, with Cromarty and the Sutors beyond; photo: Andrew Dowsett

Within the enclosure, the most westerly stone is a striking tablestone, the legs of which (as seen from remnants of paint on the less exposed parts) were painted black. The inscription covers two generations. The first two sets of initials flank a large heart shape, as do the second two sets.

Here lys the / body of ALEXR / BARKLY who / dyed March the / 27th 1765 / Also his spouse / CHRISTIAN ROSS / who dyed June the 5th 1762 / Memento mori / A B / C R / A B / C U / 1757

This stone commemorates Alexander Barkly, tacksman first in Miltown of Newhall and then tacksman of Ballicherry, on the Newhall Estate, and his wife, Christian Ross. The second set of initials are of their son, Alexander Barkly, tacksman of Kirkton Farm, again on the Newhall Estate, and later merchant in Cromarty, and his wife, Christian Urquhart. We do not yet know what the date of 1757 signifies – Alexander Barkly and Christian Urquhart married in 1760, so it is not their marriage that is being commemorated. The whole inscription was obviously carved post 1765.

The tablestone marking two generations of tacksmen named Alexander Barkly

and their wives; photo: Andrew Dowsett

As well as being tacksmen, the Barklys worked with the proprietors of Newhall and Invergordon Estates of the time, the Gordons, on deals including importation of goods without paying revenue (see our Story Behind the Stone on Alexander Elphingston, the Chamberlain of Sir William Gordon of Invergordon). Ballicherry, Kirkton and Newhall all lie close to Kirkmichael, where the Barklys held their enclosure.

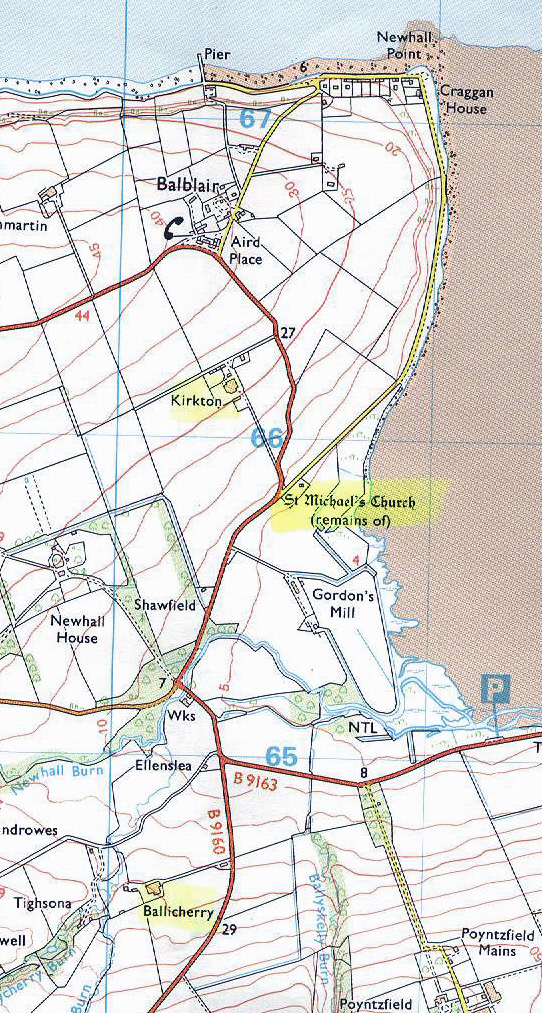

Current Ordnance Survey map showing the location of Kirkton Farm and Ballicherry in relation to

Kirkmichael

Kirkton Farm Steading guided tour 2006 by the Kirkmichael Trust. The farm had one of the earliest steam powered mills in the north, and the marvellous brick chimney is a strange sight in the countryside. Photo: Andrew Dowsett

Tucked in beside this tablestone is a small headstone with curved top, carrying the simple inscription of “I + B / G + B”. We have not yet identified the names behind these initials, but we would think the stone is in commemoration of two Barkly children.

The inconspicuous little headstone, probably put in place after the tablestones;

photo: Andrew Dowsett

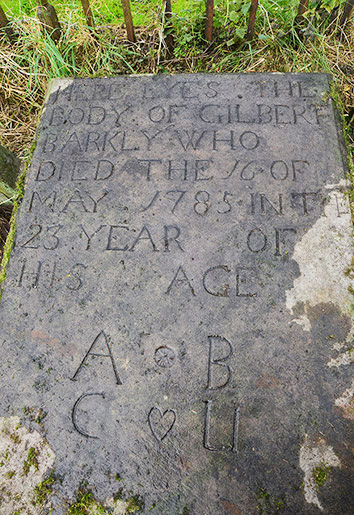

The next tablestone definitely is that of a young man dying before his time.

Here lyes the / body of GILBERT / BARKLY who / died the 16 of / May 1785 in the / 23 year of / his age / A [small circle] B / C [heart shape] U

Gilbert was a common Christian name in the Barkly family, and this particular Gilbert had been baptised in Resolis in 1761, the son of Alexander Barkly and Christian Urquhart. He had been their first child, and for him to die as a young man must have been hard for the family.

The handsome tablestone commemorating young Gilbert Barkly; photo: Andrew

Dowsett

On the far east of the Barkly enclosure is a tablestone with a rather minimalist message:

ELIZTH ROBERTSON / 1811

One has to assume that the intention was for the husband’s name to be entered on the stone in due course, but this did not occur. We can be virtually certain that this stone was erected in memory of the wife of Alexander Barkly (son of the tacksman of Kirkton, and grandson of the tacksman of Ballicherry), Elizabeth Robertson, as she is named in the baptisms to two of their children:

[Parish of Alness] 1799 … May 4 Alexr. Barkly Esq. Assynt & Mrs. Eliza Robertson had a [blotted out word, and inserted above “daugt. born on 4 May”] baptized William

[Parish of Kiltearn] Feby 9th. 1802 Alexr. Barkly Farmer in Upper Balcony and Elizabeth Robertson his wife had a son born on the 4th. baptized named AEneas.

We know no more about this particular Aeneas, but the daughter, William, married Robert Davidson, who became for a time a partner in the Davidson & Barkly company (although of an apparently unrelated family of Davidsons). She had a pretty tough time of it when her husband died in India in the early 1840s, but she was a survivor. We do not know why she was named William, but she retained the name through her life – even at her baptism, you can see that the Session Clerk had become confused.

Alexander Barkly and Elizabeth Robertson had a third child though his baptismal record has not been found. This was Hugh, who became a partner in the Davidson & Barkly company himself. He “expired suddenly in his gig at Dr. Gordon’s door, in Finsbury-square.” He must have feared early expiry as he had a will in place (PROB11/1762; 1825, with codicil 1828) and that will is most informative. “To my beloved Uncle AEneas to whom I owe every thing I possess in this world and (through means of the education he has given me) all I hope for in the next I can only offer this sincere tribute of my gratitude & sense of obligation to him and request his acceptance of the sum of One hundred pounds to purchase any memorial of me he may think proper.” In this will, written in 1825, Hugh also bequeathes an annuity to “my Grandmother Mrs. Robertson” – his mother, Elizabeth Robertson had died young in 1811, but he was providing for Elizabeth’s mother, his grandmother, who clearly was still alive at that time.

The Elizabeth Robertson tablestone. Photo: Andrew Dowsett

and her inscription – what happened to her husband, Alexander Barkly? Photo: Andrew Dowsett

Update December 2020: We are indebted to Dr David Alston who has shared with us a finding from his researches. This solves the mystery of what happened to the husband of Elizabeth Robertson, Alexander Barkly, farmer in Upper Balcony. The information is found within a letter written by Anne Robertson, wife of the Reverend Harry Robertson (relative of Elizabeth Robertson?) from Kiltearn manse to her daughter in March 1805 (“Letters of Harry Robertson, and his wife Anne, chiefly to their daughter, Christy Traill, but also to her husbands, James Watson, and Thomas Stewart Traill” – NLS MS 19331 f98v). She says:

But when we consider the case of others we have many consolations – to compare this with the shocking and [un]timely exit [of] Mr Barkley. I assure you for some time this rash deed, cast a horror on all this neighbourhood. Unfortunate man that had not fortitude to stand the shock a little longer for by letters since his death from his Bror Eneas he was ready to come forward with every assistance and with 500 st in the first instance. I hope from this he will sympathize with his unfortunate Widow and her Family, poor woman she is as well as could be expected from her deplorable circumstances.

It is only too clear what must have happened. Alexander Barkly had fallen into desperate financial difficulties, and instead of asking his brother Aeneas for assistance, had taken his own life. This must have occurred in February or March 1805, as he is mentioned in those months in advertisements promoting the sale of the nearby farm of Mountrich – “The farm will be shewn by Mr Denham, of Dunglas, and Mr Barkly, at Balcony, both by Dingwall”. As we have seen, Aeneas did indeed step in and provide for the children, although poor Elizabeth Robertson was to die a few years later in 1811. Suicide at this time was anathema, and in a well documented case, as recently as 1844, one Kinbeachie farmer who had committed suicide was buried by his relatives on the moor-ground in the Mulbuie rather than in the graveyard at Cullicudden. We can assume then that the solitariness of “ELIZTH ROBERTSON / 1811” on the tablestone in the Barkly enclosure is because his name was not entered as his death, before his wife’s, was a suicide.

And the final stone found so far in Kirkmichael is also a rather sad one, devoted presumably to another set of children who did not survive to adulthood. It is not within the enclosure, and is in fact a slab of uncompromising rectangular design. Only a small corner now protrudes from the grass, but was it intended as a tablestone? Notice the date at the end: 1757, the same as on the first tablestone inside the enclosure, with similar carved style. This cannot be coincidence.

Here / lys / the bodys / of GEORGE / CHARLES / BARBARA / BARKLYS / children to / ALEXR BARKLY / who lived in Balech-- / Placed by / A • B / 1757

There is a gap after “Balech” and it is assumed that “ry” has been eroded from the original “Balechery”. George was baptised in 1776, but we have no record of the baptism of Charles or Barbara – indeed, we have no record of the baptism of any of the daughters of Alexander Barkly and Christian Urquhart. We have Gilbert (1761), John (1763), Alexander (1766), Eneas (1768), William (1769), John (1772), David (1774) and George (1776). For some reason, published sources state that Alexander Barkly had five sons and four daughters, with Aeneas being the youngest son, but clearly this is incorrect.

A corner protrudes… Photo: Andrew Dowsett

and the inscription revealed. Photo: Andrew Dowsett

These gravestones and in particular the tablestones indicate that the Barkly family were well off. Most families in the later half of the 18th century/early 19th century could not afford any sort of gravestone let alone an inscribed memorial. The inscriptions provide a glimpse into the past about this family and help supplement the few references found in the Parish Records, but who were the Barkly family? Barkly has always been a fairly rare surname in Scottish and English records, and has possibly disappeared altogether from Scotland to day. The Barkley name is not quite so rare. Local records and in particular later published family histories and specific biographies about the different branches and members of the Barkly/Barkley family have allowed us to begin to document the history of this family.

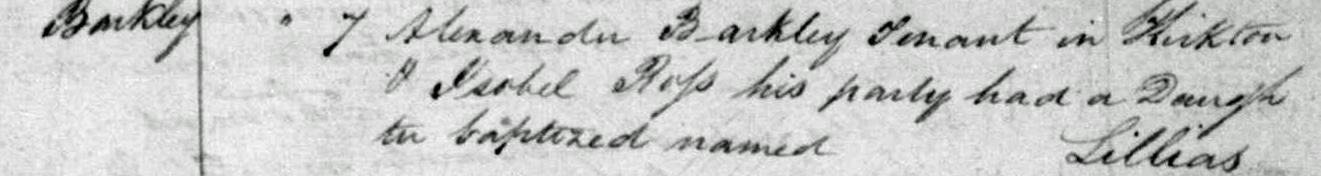

The Newhall estate records, Kirkmichael memorial inscriptions, Resolis parish records and many charters refer to Alexander Barkly senior and junior and their wives. There is one anomaly, however: a 7 September 1758 baptism: “Lillias Barkley, daughter of Alexander Barkley, tenant in Kirkton, and Isobel Ross, his party”. Now, when the Resolis baptism register refers to “his party” instead of “his spouse” it usually (although not always) means that the child was born out of wedlock. We cannot tell if this was the case here for the Kirk Session minutes are not extant for this period, but we can certainly add another child to his family. Intriguingly, Lillias must have been conceived in the year 1757 … the same date marked on two of the Kirkmichael stones.

The unusual entry in the baptism register

It is reported in published sources, presumably from the family records in the National Library of Scotland (Acc. 9907), that Alexander Barkly in 1788 left the farm at Kirkton to move into Barkly House in Cromarty, after a family dispute with his in-laws, the Urquharts “who owned the farm as well as other land in the area.” His wife was of the family of Urquhart of Mount Eagle, near Fearn in Easter Ross, and we are not sure if the quotation is strictly correct. Barkly House still exists, having been extensively rebuilt recently after being empty and derelict for many years following a fire. His grave and that of his wife have not yet been found but they may have been buried in the Kirkmichael graveyard.

Barkly House before its disastrous fire which left it a roofless shell; photograph from Mona

Macmillan’s Sir Henry Barkly

and Barkly House following its restoration. Photo: Andrew Dowsett

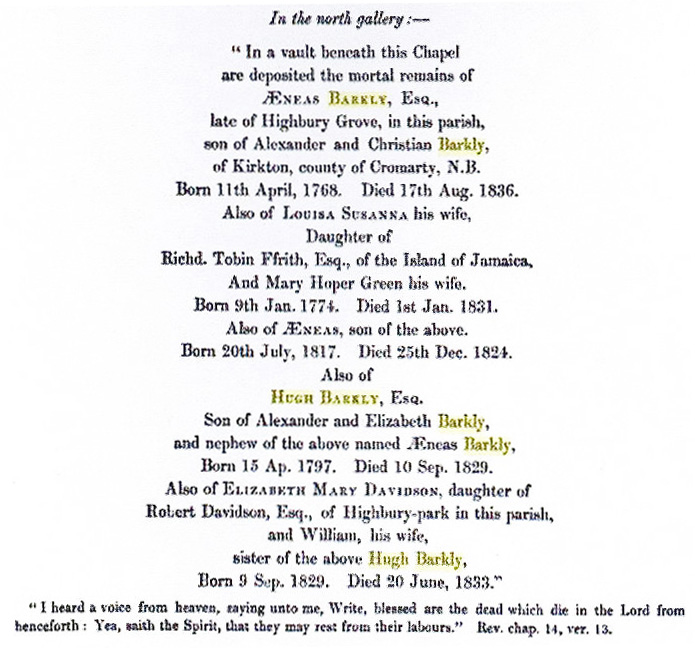

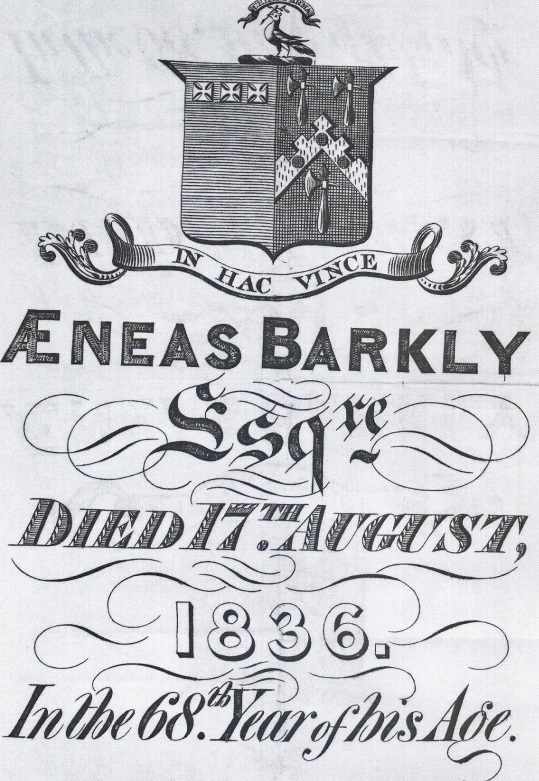

Aeneas Barkly (1768–1836)

We owe much of our knowledge about this line of the family to the research carried out in recent years covering the life of Alexander Barkly’s son Aeneas Barkly 1768–1836, who left Cromarty and became a very successful London West India merchant, ship owner, and plantation owner. Aeneas became a partner with Henry Davidson of Tulloch to form Davidson, Barkly & Co one of the largest West India trading businesses in London prior to the ending of slavery and the plantation operations in the West Indies. Henry Davidson’s family also came from Cromarty. Aeneas supported his parents and his siblings who remained in Cromarty.

Aeneas and his wife were buried in Islington, close to their home in Highbury in North London. The transcription of their detailed monumental inscription has survived but the grave has not been found. And yes, the lady called William Barkly who married Robert Davidson esquire, as mentioned in the memorial, is she who was born in Alness in 1799.

We have also found evidence that Aeneas Barkly and his family used heraldry. This item has been found within the family papers held in the National Library of Scotland, in Edinburgh. We have no evidence that these arms were ever registered at the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh or the College of Arms in London.

Transcription of Barkly memorial

Aeneas Barkly family crest

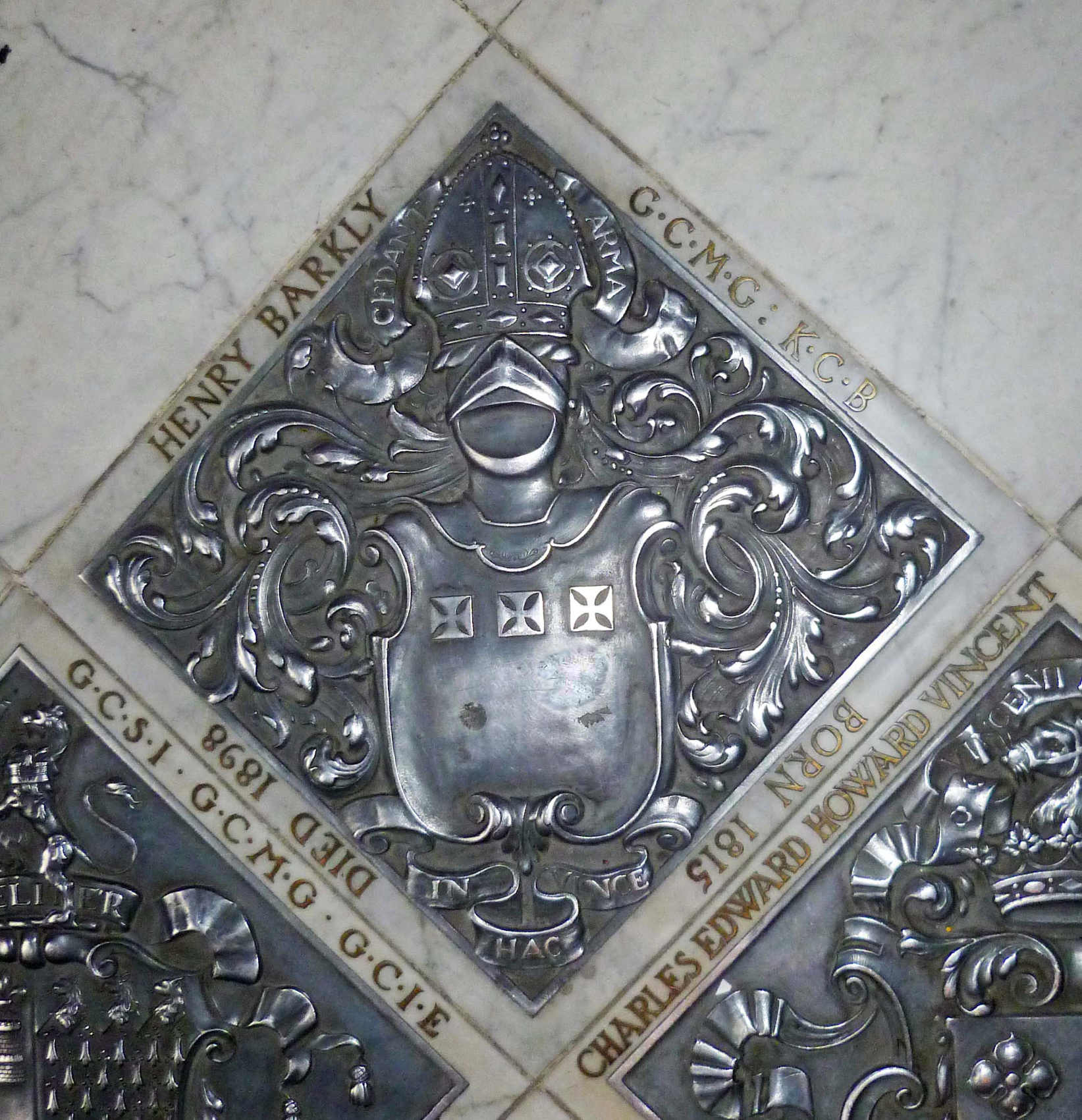

Sir Henry Barkly (1815–1898)

Aeneas Barkly died in 1836 leaving his only surviving son Henry Barkly 1815–1898, not yet 21, to sort out his financial affairs, which took several years. Eventually Henry broke up the business partnership with the Davidson of Tulloch family, served as an MP, and later enjoyed a long career as a distinguished Colonial Governor in the West Indies, Australia, and South Africa.

Portrait of Sir Henry Barkly by Thomas White, c1864, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra,

Australia; photo: Nick Hide

St Paul’s Cathedral – Sir Henry is commemorated in the permanent display set in the floor of the Chapel dedicated to the Order of St Michael & St George; photo: Nick Hide

The late Mona MacMillan’s biography Sir Henry Barkly published in 1970 in South Africa covers his career in great detail as well as providing family history and information on the family roots on the Black Isle. Some of that information could be amended and added to today because of our ability to access a wider range of archival records than were available to the author.

It was Sir Henry Barkly’s career as Colonial Governor which caused the Barkly name to appear in South Africa where settlements such as West Barkly in the Northern Cape and East Barkly in the Eastern Cape were founded in his name. Similarly in Australia, there are several different streets named after him from his time as Governor of Victoria.

Henry Barkly was also very interested in the natural sciences. He was in touch with Kew Gardens throughout his overseas career. There are several botanical species named after him such as Barklya F. Muell, a fine flowering tree native of Queensland, Stapelia barklyi N. E. Br found in South Africa, and Salaginella barklyi Baker found in Mauritius.

Gilbert Barkly (c1730–1799)

Alexander Barkly the tacksman of Kirkton, Balblair, had several brothers and sisters. One of his younger brothers was Gilbert Barkly (c1730–1799). The late Eric Malcolm’s book Heroes… and Others who left Cromarty for even wider skies (Cromarty Courthouse Publications, 2003) devotes a whole chapter to this member of the family. He enjoyed a short career as a merchant of Cromarty, undertook fraudulent dealings in Scotland and Europe, went bankrupt, was imprisoned for debt at Elgin in 1754, escaped and later fled to North America. There are several reported anecdotes about his early career which characterise him as desperate character, a smuggler, suspected of piracy, and even accused of murder.

In North America, he was soon back in business as a trader and merchant. In the early 1770s as the unrest grew among the American colonists, Gilbert was approached by the British government during a visit to London to provide information about the situation in the colonies. On his return to North America, he spent the next few years watching and reporting in dismay as the American Colonists gained the upper hand in their fight for independence. The archives are full of the accurate reports made by this spy. Sadly the years he spent warning the authorities in London appear to have gone mostly unheeded.

Gilbert married Ann Inglis in Philadelphia in about 1761, and eventually retired to Walcot, Bath, where he died in 1799. Gilbert was maybe not a Hero… but he was certainly one of the “Others who left Cromarty for even wider skies”.

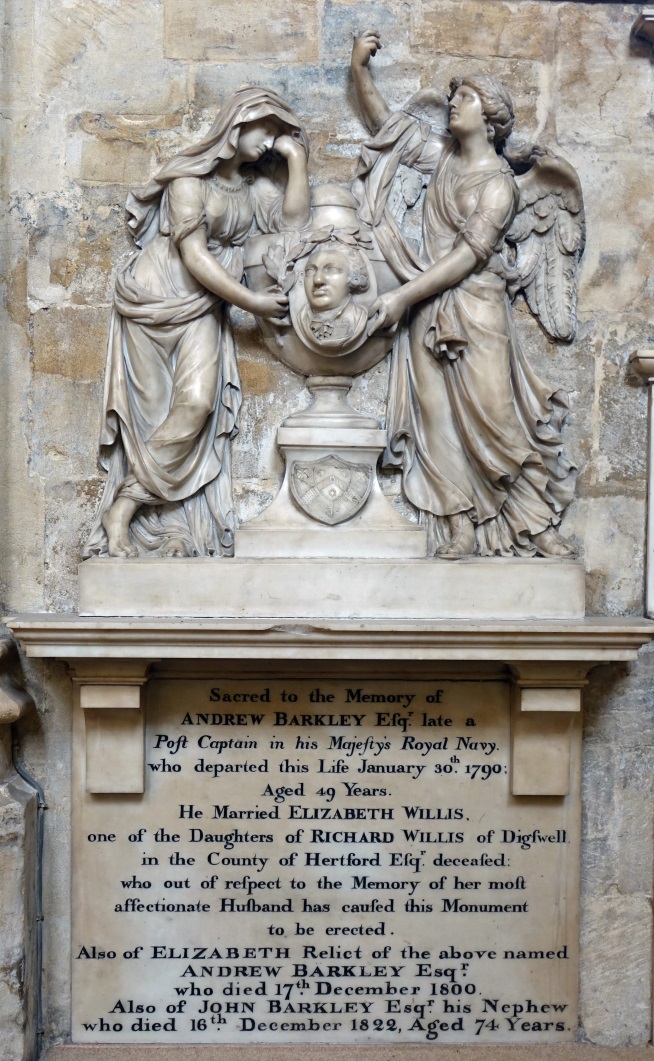

The Barkley Brothers

Eric Malcolm also highlighted another related branch of the Barkly family from Cromarty. This branch tended to spell their surname as BARKLEY. Three brothers Andrew, William and Charles Barkley were apparently all born in the Cromarty area in the first half of the 18th century. They left the Black Isle to find their own way in the world.

William Barkley (–1807) became a lawyer in London with homes in Bedford Square, London, Sunbury on Thames, and Bath. He died in 1807. He was twice married but there is no evidence of any surviving children.

Andrew Barkley (c1741–1790), rose to the rank of Captain in the Royal Navy and had a distinguished naval career. He married Elizabeth Willis in London in 1786. After Andrew died, she married one of Andrew’s nephews John Barkley (1749–1822), a former shipmaster. Neither Andrew nor his nephew John left any surviving children. The Barkley family installed a fine memorial monument to Andrew, his wife, and his nephew John Barkley in Bath Abbey.

Barkley memorial in Bath Abbey; photo: Nick Hide

Elements of the Barkley memorial; photo: Nick Hide

Charles Barkley (c1718–1774) became a Captain with the East India Company’s Maritime service but sadly died at sea. The Remarkable World of Frances Barkley suggests he died in the Hooghly River, Calcutta, in 1776. However, descendant and correspondent Madeleine Symes has investigated the true story in the British Library in London, in the East India Company records for the “Pacific”, Captain Charles Barkley’s ship on his journey 1773/4. The Journal states: “From Ceylon to Madras. Sunday 14 August 1774. … At 3am Departed this life Captain Charles Barkley of a fever – having been ill six days only – at Noon committed his Body to the Deep”. The Journal mentions the ship being near a mountain – Friars Hood, Ceylon – visible from the ship. The Journal states he was succeeded by James Williamson Chief Mate, who writes the Journal.

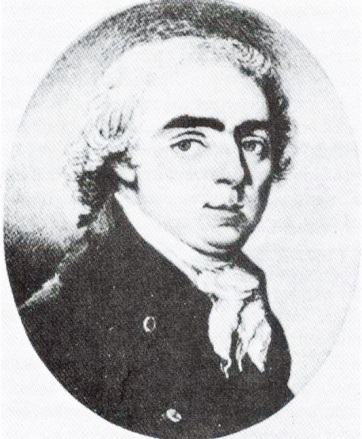

Captain Charles Barkley’s son Charles William Barkley (1759–1832) was already in the service. In 1786, he resigned and became a shipmaster on his own account as an independent merchant/shipmaster. This was the start of an extraordinary career in which he crossed the oceans many times as a trader explorer. His wife Frances Hornby Trevor whom he married in Ostend at the start of his independent career travelled with him for eight years and some of their children were born at sea. It was very rare for a shipmaster’s wife to travel with her husband at that time. The transcriptions of her diaries and the family letters have survived (see The Remarkable World of Frances Barkley by Beth Hill and Cathy Converse (Heritage House Publishing Co Ltd, 2003) – it can still be obtained on Amazon). The couple suffered many trials such as the death of a child, the loss of Charles’ ship and cargo, imprisonment, and ship-wreck. However it was their unique early trading explorations of the Northern Pacific coastland of North America which should be remembered. Barkley Sound off Vancouver Island is named after Charles William Barkley. The family later settled at Bath, and then at Hertford.

Charles William Barkley from The Remarkable World of Frances Barkley by Beth Hill and

Cathy Converse.

In 1810 Charles William Barkley travelled to Cromarty by sea in an attempt to resolve a long standing family dispute about a Cromarty property named as Shingleside. This dispute apparently stemmed from the time of Alexander Barkly, the tacksman from Kirkton, Balblair, mentioned above, who had acquired or taken possession of the property incorrectly. The property in question has not been located… was Shingleside the same place as Barkly House or was it some other property? Alexander Barkly’s son, Aeneas Barkly, the successful London merchant, appears to get the blame by the time Charles William Barkley visits Cromarty. Charles William Barkley was given assistance when he reached Cromarty by – the young Hugh Miller. The dispute was never resolved, mainly because the relevant parish records could not be found, although the sasine records set out the boundaries of the Barkly properties in Cromarty, and can yet be critically appraised.

The dispute did have one useful outcome: it provides us with the proof that the Barkly and Barkley families from Resolis and Cromarty were connected.

.A complementary Story Behind the Stone here examines the early Black Isle origins of these enterprising Barkly and Barkley families and another here explores how the Barkly family came into Mounteagle.